Movies in the Dark: The occupation's film culture

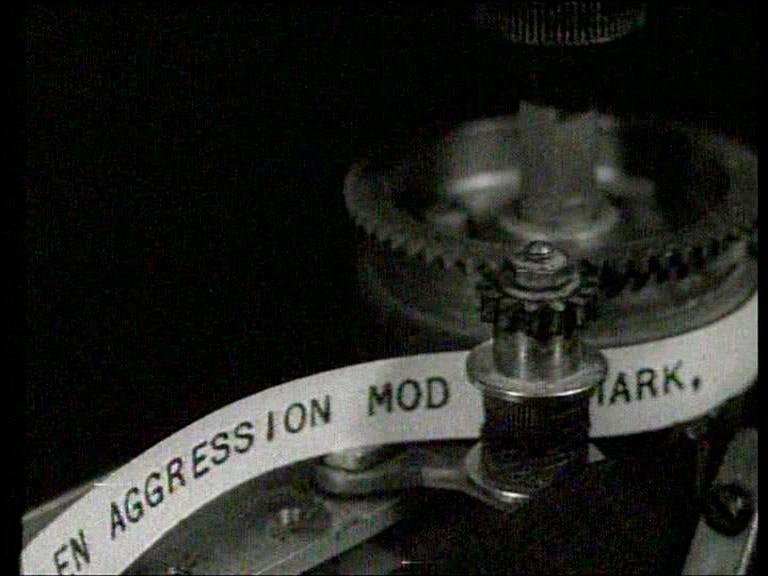

With the German occupation of Denmark in 1940, Danish cinema was placed under the occupier's directives.

The Germans controlled all production companies' access to raw footage and determined the repertoires at the movie theatres. Many more German films were now shown in the theatres (at one point every other film shown at Copenhagen's premier theatres was German), but films from the allied countries were first banned at the end of 1942.

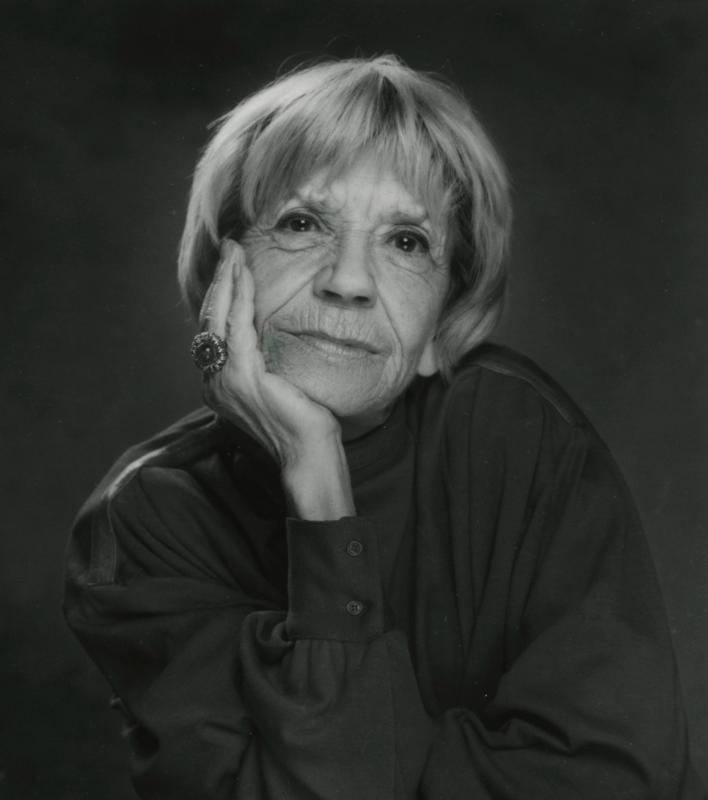

The Danish films produced during this period, it goes without saying, could not put forth a critique of the occupying power, and the films avoided almost all references to the actual situation, but they clearly changed character. Criminality and suspense had up until now been absent from Danish talkies (The Vicar of Vejlby was an exception). But now it was the darker films that succeeded, among them were Bodil Ipsen and Lau Lauritzen Junior's dark psychological Afsporet (1942), produced by the company Apollon-Film at ASA, and the thriller film The Melody of Murder (1944) with traces of French poetic realism and American film noir.

Danish cinema as a whole became more internationally orientated. The comedy genre moved away from the traditional people's comedy and began to follow the more sophisticated American screwball comedy a la Lubitsch as seen in Bodil Ipsen's A Gentleman in White Tie and Tails (1942), but especially Johan Jacobsen, stands out as one of the leading directors with comedies such as My Dear Wives and Som du vil ha' mig - ! (both 1943). His elegant episodic film Eight Chords (1944), about a gramophone record that goes from hand to hand, took its structure from Julien Duvivier's French Un carnet de Bal and American Tales of Manhattan.

At the same time a larger focus was put on national issues. Svend Methling's classic The Joys of Summer (1940), based on a novel by Herman Bang, painted both a touching and satirical picture of a former Danish province viewed via a collection of people; Emanuel Gregers' Sørensen og Rasmussen (1940) jovially tells the story of the Danish King Frederik VII and his unofficial wife's visit to a manor. In addition came Schnéevoigt‘s biographical I Have Loved and Lived (1940), about the composer Weyse from the 1800s romantic golden age in Danish culture, and Tordenskjold Goes Ashore (1942) about the naval hero from the 1700s.

Dreyer's Day of Wrath (1943), with its portrayal of torture and witch trials in the 1600s, can be read as an indirect commentary on Nazism, even if that wasn't Dreyer's intent. On the other hand, there is no doubt that Hagen Hasselbalch's documentary short The Corn is in Danger, which was released in April 1945 shortly before the Danish liberation, while seemingly a regular information film about the battle against the corn nose beetle, was also a subtly witty fable referring to the German occupation.

Film poster from the 1940s

Emancipation and escape: Documentaries and experimental films of the 40s

During the occupation short documentary films became the norm as short subjects before the feature film in movie theatres, where they replaced the unpopular German weekly reviews (an ordinance that the Ministeriernes Filmudvalg, 1944-66, established), and this especially provided opportunities to young directors.

Bjarne Henning-Jensen's Brown Coal (1941) and Paper (1942) and Ole Palsbo's Waste is Money (1942) were instructively modelled after British documentaries. Much like the producer John Grierson, who among other works was behind the trendsetting Night Mail (1936), Danish documentaries gambled on combining information, poetry and aesthetics. For example, in films such as Karl Roos' Under a Thatched Roof (1942), about the Danish open air museum and peasant life in older times, Theodor Christensen's People in a House (1943), about social problems and the institutions that can solve them, and Hagen Hasselbalch's Shaped by Danish Hands (1948), about Danish craftsmen.

After the war came Theodor Christensen's, controversial chief work Your Freedom is at Stake (1946), which with satirical strokes criticized the Danish government's political collusion with the occupying German power. Dreyer also made a number of documentaries in this period, among them the socially engaged Good Mothers (1942), about unwed mothers' situations, his first film after a long involuntary break, as well as Thorvaldsen (1949), a film about the classic Danish sculptor.

It was also in this period that Danish experimental films got their start. Theodor Christensen and Karl Roos wrote a manuscript for the historical adventure story Jens Langkniv (1940), which tried to give Danish cinema a little avant-garde filmic language, inspired by Russian montage, but unfortunately an unsuccessful attempt. Otherwise, like in many other countries, it was the painters who stood behind the experimental short films. Documentary filmmaker Jørgen Roos, worked together with painter Albert Mertz on the short Escape (1942), a modernist study in seven minutes, and Roos continued to make lively short films with the surrealist Wilhelm Freddie such as Det definitive afslag på anmodningen om et kys (1949) and Spiste horisonter (1950).

Everyday life returns: Post-war realism in Danish cinema

Denmark was liberated in May of 1945 by British forces, and before the year was out two Danish feature films about the Danish resistance movement and sabotage were made. Bodil Ipsen and Lau Lauritzen Junior's The Red Meadows and Johan Jacobsen's The Invisible Army, which was followed up by the collaborationist drama Tre år efter (1948).

Henceforth Danish cinema delved into a more realist direction, a critical humanitarian realism with a focus on everyday fate, not incomparable to Italian neo-realism; cultural issues were also focused upon. Ole Palsbo showed sharp social and psychological analyses in Discretion Wanted (1946), about a sanctuary for unmarried pregnant women, and especially Take What You Want (1947) with its portrayal of a cynical climber's career. Bjarne Henning-Jensen‘s beautiful Ditte, Child of Man (1946), based on Martin Andersen-Nexø's classic and socially indignant novel about the fate of a girl from an aging small town milieu. Henning-Jensen together with his wife Astrid made both the intense psychological criminal drama Kristinus Bergman (1948), and the comedy Those Damned Kids (1947), the first Danish children's film. In the same vein Astrid Henning-Jensen continued on alone with the short children's film Palle Alone in the World (1949, first shown in Denmark in 1954), which still stands as a classic.

A chief work was Johan Jacobsen's Jenny and the Soldier (1947), which with engaged realism portrays social injustices through the story of two everyday losers' fates, played by the new stars Poul Reichhardt and Bodil Kjer. The movie was produced by the company Saga Film, which was started in 1942 with John Olsen as its leader. The company was also behind the noir-ish film John and Irene (1949), where Bodil Kjer and Ebbe Rode play travelling dance partners who are dragged into a world of crime and ruin.

An example of an atypical production during the period can be found in the feature length animation The Tinder Box (1946), the first Danish colour film, based upon H.C Andersen's fairy tale.