The Danish Film Institute

With the Film Law of 1972, the Film Fund was transformed into the Danish Film Institute (still part of the Ministry of Culture); from then on this became the organizational support tool for all national films. For the first time film was directly placed in the state budget. This was done primarily through the so-called consultant scheme where state aid decisions were made by consultants, who were hired for two to three years. In the early years there were two consultants for movies for adults and from 1976 on, one for children and youth films. In 1988 there was an extra consultant used for short films and documentaries and from 1989, a consultant for short children's films and documentaries. The new film law also abolished the appropriation system whereby the ailing movie theatre industry became a free market.

The Film Law and state support to Danish cinema worked as a bailout for the art form, but it could also be seen as government intervention into artistic freedom, which is why it was important that the DFI (Danish Film Institute) could work independently of the political power, the so-called "at-arms-length" principle.

Cultural Provocations: the Thorsen case and the avant-garde

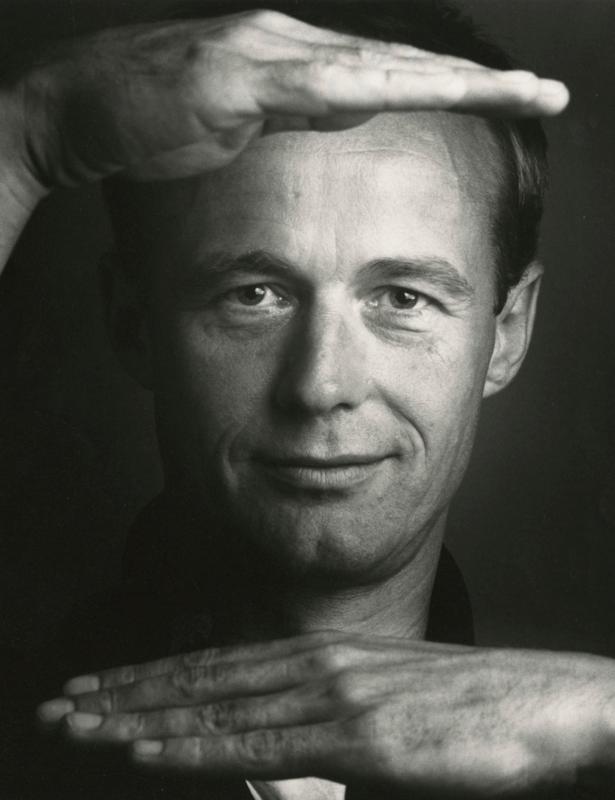

The new consultant system ran into trouble from the very beginning precisely regarding its independence and integrity. Jens Jørgen Thorsen, known as a painter, happening-artist and director of the Henry Miller adaptation Quiet Days in Clichy (1970), announced, that he would make a film about Jesus, 'The Many Faces of Jesus Christ', where the saviour was to be presented as a political and erotic activist.

The screenplay in 1973 was recommended to receive support from consultant Gert Fredholm, but the case incited such a furore–also internationally, the Pope himself protested – that the DFI halted the project. It was reinstituted for support in 1975, this time by consultant Stig Björkman, but was stopped on direct orders from Minister of Culture Niels Matthiasen, referring to the suspicion that the work could be blasphemous and in violation of the evangelist copyright (!). Regardless of artistic freedom of expression it was not agreeable to have Christianity mocked and made fun of. But the ministerial decision was deemed illegal–in 1989.

Thorsen had roots in the period's provocative, alternative culture, which had already marked itself through controversial works. From the artistic movement ABCinema came the cooperative film Without Kin (1970) with contributions from, among others, Per Kirkeby, Jørgen Leth, Ole John and Bjørn Nørgaard, in it is the famous scene in which Lene Adler Petersen as a naked, female Christ figure bears the cross through the Stock Market. An initiative towards the democratization of access to the media arrived with Filmværkstedet, established in 1970 (as Workshoppen, since Det Danske Filmværksted), to provide support to films, first and foremost documentaries and experimental films, which wouldn't otherwise be produced by normal productions. Mainly socially critical and political shorts were produced there, for example the feminist The Sleeping Beauty (Tornerose var et vakkert barn, 1971) by Jytte Rex and Kirsten Justesen.

Realism, debate and heritage: Feature films in the 70s

A new realism begins to enter 1970s Danish cinema. Franz Ernst's Concerning Lone (1970) tells a story, in semi-documentary style, about a young girl who runs away from both the established community and the alternative community. The portrayal of reality was also central in Hans Kristensen's films dealing with the small time crook and misfit Per (Ole Ernst), in films such as The Escape (1973) and Per (1975). Henning Carlsen's Oh, to Be on the Bandwagon! (1972), which – with a screenplay by Benny Andersen – focused on melancholic nightlife dwellers, as well as Astrid Henning-Jensen's Winter-born (1978) based upon Dea Trier Mørch's success novel about women in a maternity ward.

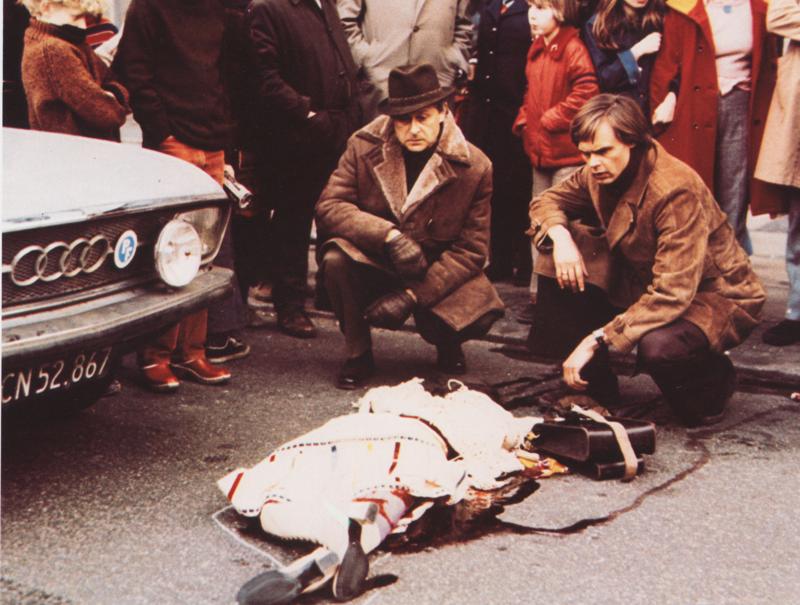

Realism was also a hit for the crime genre, which until now was a rarity in Danish films. Esben Høilund-Carlsen's Nineteen Red Roses (1974) is the first modern crime film with blood, action and an American influence. Anders Refn continues in the same style with the cop film Copper (1976), Erik Crone produced both.

There are also films that enter into the political and women's rights debate such as Christian Braad Thomsen's Dear Irene (1971), Peter Refn's Violets Are Blue (1975) and especially Mette Knudsen, Elisabeth Rygård and Li Vilstrup's Take it Like a Man, Ma'm (1975), which in its deftly portrayed dream sequence, the gender stereotypes are switched and we see a subjugated man working at home, and a swaggering woman working outside the home. An intellectual debate is touched upon by Henrik Stangerup, who beside his authorship, developed as a director with Give God a Chance on Sundays (1970), about a priest in a religious and marital crisis, as well as the psychiatry film It Happens in Denmark (1972) and the bold but unsuccessful The Earth is Flat (1977), which relocated Holberg's classic play Erasmus Montanus to Brazil in the 1700s.

Literary heritage was also addressed in Knud Leif Thomsen's The Liar (1970), based on Martin A. Hansen's existentialist novel; Claus Ørsted's The Work of the Devil (1972), based on Blicher; Ole Roos' Vandalism (1977, with a screenplay by Klaus Rifbjerg), based on Tom Kristensen's modernist alcoholism novel; Anders Refn in The Baron (1978), based on Gustav Wied and finally Gert Fredholm's successful The Case of the Missing Clerk (1971), which updates Hans Scherfig's satirical novel about the bourgeois society.

Outside these trends one finds Edward Fleming, with the comedy debut – And there's Dancing Afterwards (1970), about actors on a provincial tour, also the occupation drama Brief Summer (1976) and the transvestite and homosexual comedy Mirror, Mirror (1978).

On the children's side: Youth film's heyday

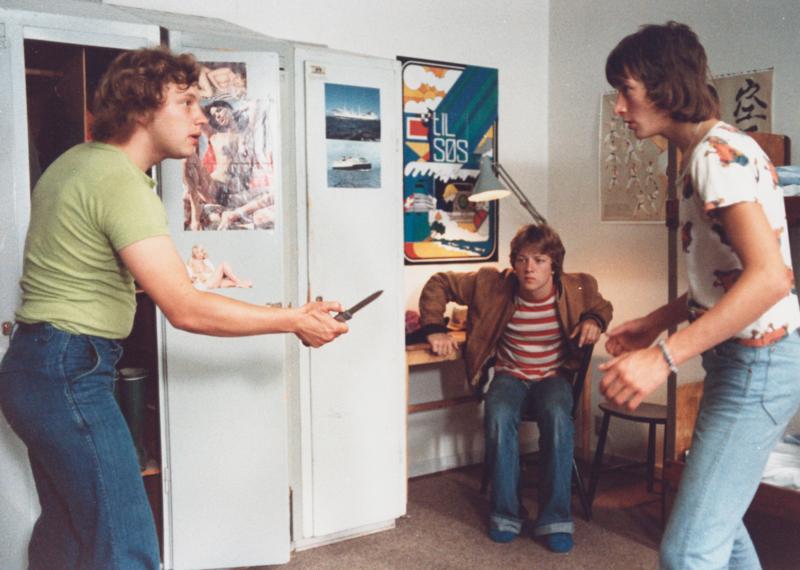

In this period there is one particular genre that breaks through and experiences a golden age, the youth films. Where youth films in the 50s held a moral distance to the amoral and irresponsible younger generation, the 70s youth films were quite loyal and sensitive to the marginalized young, who stood hesitant and perplexed about the challenges of adulthood.

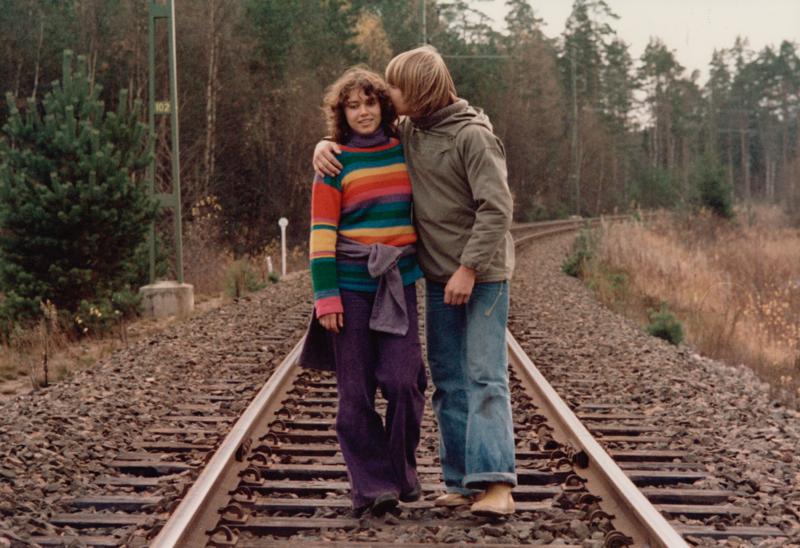

It started with Lasse Nielsen's Leave Us Alone (1975, co-director Ernst Johansen), Morten Arnfred's Me and Charly (1975, co-director Henning Kristiansen) and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen's Wanna See My Beatiful Navel? (1978), all the above produced by Steen Herdel. These were followed by Morten Arnfred's exemplary Johnny Larsen (1979), which distinguished itself with cinematographer Dirk Brüel's atmospherically packed images. Also Bille August's first film, In My Life (1978), dealing with the fragile lives of two young individuals, shows the same sensitivity towards vulnerable youth. With these movies youth film became an iconic brand for Danish cinema.

It's also in the universe of children and youth films that a rather exceptional auteur finds his beginnings. The self-taught Nils Malmros' Lars Ole, 5c (1973) and Boys (1977) can also be viewed as more adult works, where the director with eminent empathy and emotionally commemorative artfulness reconstructs the hopes and pains of childhood and adolescence from his hometown of Aarhus.

Youth cinema is exploited more commercially in films such as Edward Fleming's Traditions, up yours! (1979) based on Leif Panduro's neo-classic breakthrough novel.

In the animation world, Jannik Hastrup and Flemming Quist Møller's Benny's Bathtub (1971) appears, a film in which a boy finds an escape from life in the dreary concrete housing projects around him by using his imagination to go on adventures. It was the definitive breakthrough for a culturally satirical animated movie style, one that takes a demonstrative distance from the classic, more sugary Disney style.

Life in Denmark: 70s Documentaries

The government's Film Central, started in 1938 for the distribution of documentaries, became part of the DFI with the enactment of the 1972-law and became the country's central producer of documentaries.

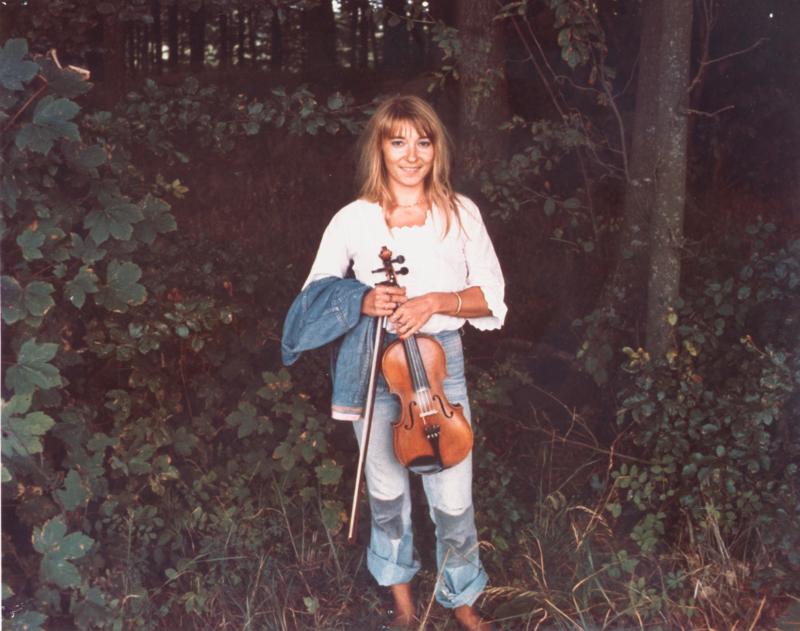

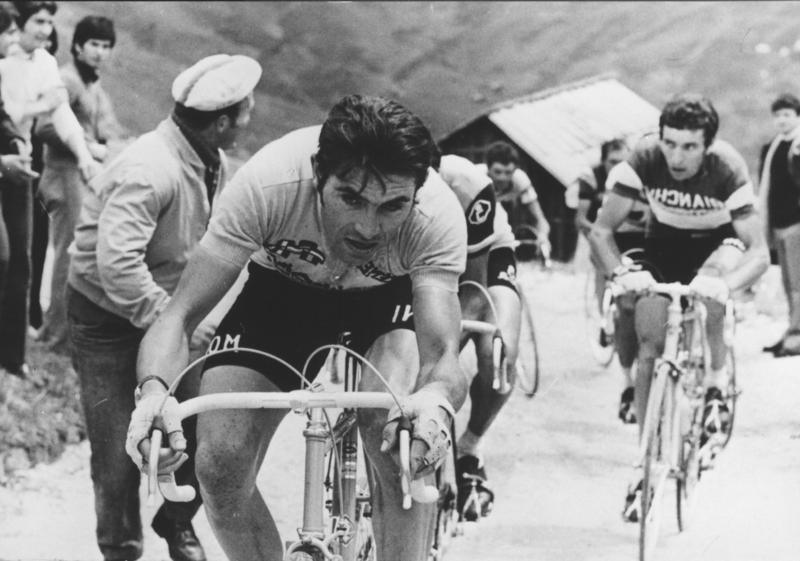

Among the period's most important documentarians are Jon Bang Carlsen with the portraits Jenny (1977) and A Rich Man (1979), Frantz Ernst with Livet er en drøm (1972), about the mentally ill, Christian Braad Thomsen with a homeland portrayal Well-Spring off My World (1976), Jørgen Vestergaard with 'Dengang jeg drog af sted' (1971), about the draft, and Den store dag (1975), about confirmations. Claus Ørsted and Lars Brydesen made a Denmark film with Danske billeder (1970, script by Klaus Rifbjerg). Jørgen Leth continued in the same vein with his chief work Life in Denmark (1971), which depicts the nation in the form of a kind of anthropological catalogue. He also drew attention with the bicycle sport movies Stars and Water Carriers (1973) and A Sunday in Hell (1976).

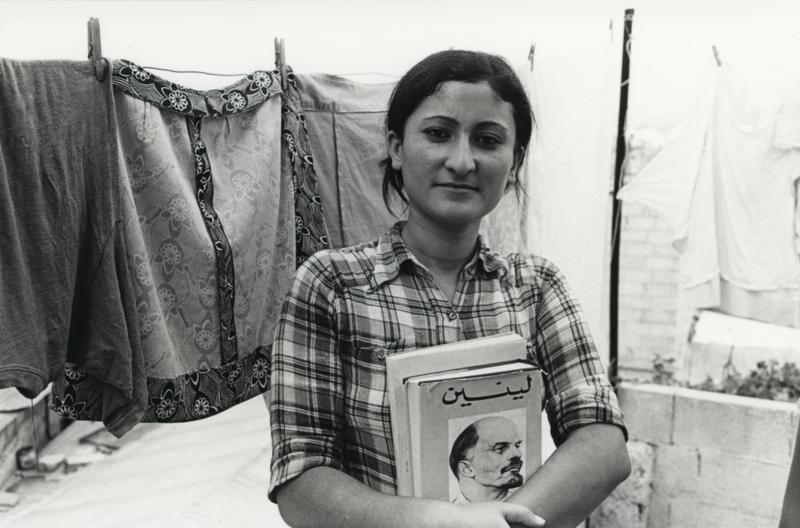

Political documentaries are represented by Nils Vest's Et undertrykt folk har altid ret (1976), about the Palestinian problem, and Jørgen Flindt Pedersen and Erik Stephensen's Your Neighbour's Son (1981), about the executioners of the Greek junta regime.

Film posters from the 1970s

The sexual folk comedy: Bedside films and zodiac films

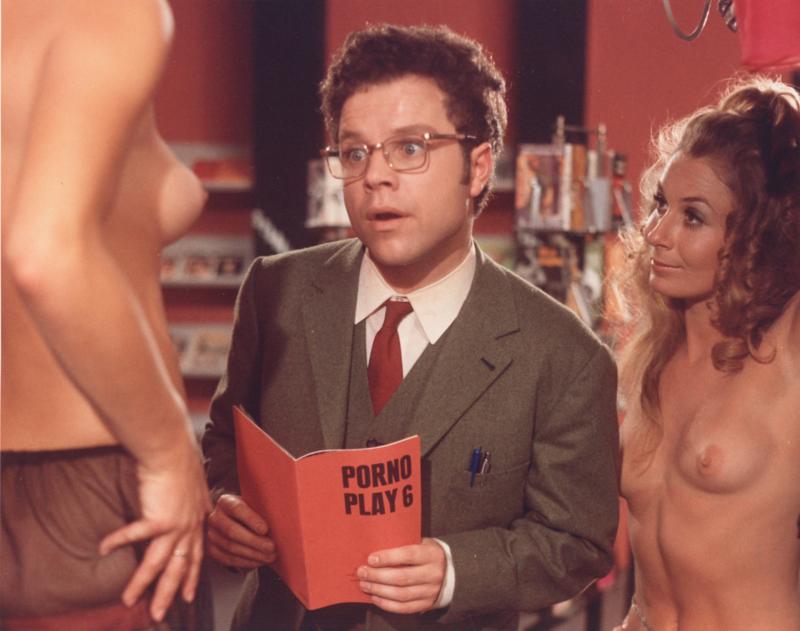

The removal of censorship of pornographic images in 1969 immediately led to the production of, more or less, explicitly erotic film that for a short while created a worldwide sensation around Danish cinema.

Through the decade, the old, illustrious Palladium made eight so-called "bedside" films, a kind of erotic (and mildly pornographic) folk comedies, which began with John Hilbard's Bedroom Mazurka (1970). A rival series were the so-called zodiac films (the most of which were directed by Werner Hedman for the companies Con Amore and Happy Film), beginning with In the Sign of the Virgin (1973); they were films of a similar character but with much more explicit erotica and spots of hardcore pornography. Featured in both series was Ole Søltoft lead actor, typically portraying a shy, innocent man who is tempted by, among others, Annie Birgit Garde and Birte Tove, and there were both noteworthy actors and anonymous sex actors in the credits.

The erotic films, which also included Ole Ege's The Bordello (1972), and received backup support from Gabriel Axel with films such as Amour (1970) and With Love (1971), became a solid export and have remained time-typical national kitsch, where the new sexual liberation met the conventional Danish folk comedy.

The Olsen Gang: folk comedy's last coup

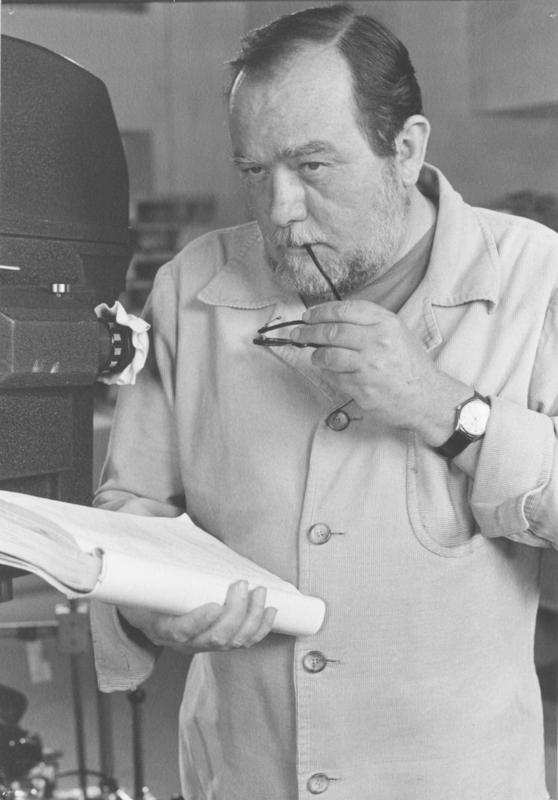

After a down period in the 60s, folk comedy (without an erotic agenda) achieved a revival in the 70s with, first and foremost, Nordisk Film's and Erik Balling's cheerful heist movies about the Olsen Gang, which had Henning Bahs as indispensable co-author, set designer and special effects man.

It started with The Olsen Gang (1968) and The Olsen Gang in A Fix (1969) without achieving much success, but with The Olsen Gang Plays for High Stakes (1971), the concept found just the right form, and up through the 70s the series (with 13 films in all, 1968-81) was the country's most popular film entertainment.

The brilliant, but always-unlucky, gang leader Egon (Ove Sprogøe) and his two hopeless assistants, the wimp Kjeld (Poul Bundgaard) and the dopey Benny (Morten Grunwald), summarized, in the eyes of Denmark, some typical national characteristics, but at the same time achieved a cultish following in, among other places, DDR (German Democratic Republic).

Balling and Nordisk Film joined together with Danmarks Radio and went into tv-production, making the comedy series Huset på Christianshavn (1970-77) and the one of a kind, popular serial Matador (1978-82 creator Lise Nørgaard), which, with its portrayal of life at both the top and the bottom of a Danish provincial town in 1929-47, became a cultural and communal focal point for the nation.

Read more about the films