The irony was thick when the Zimbabwean government banned a documentary chronicling the writing of the country’s first democratic constitution. This, despite the fact that the film doesn’t take sides or directly criticise dictator Robert Mugabe, who until his ouster on 19 November 2017 had ruled for more than 30 years.

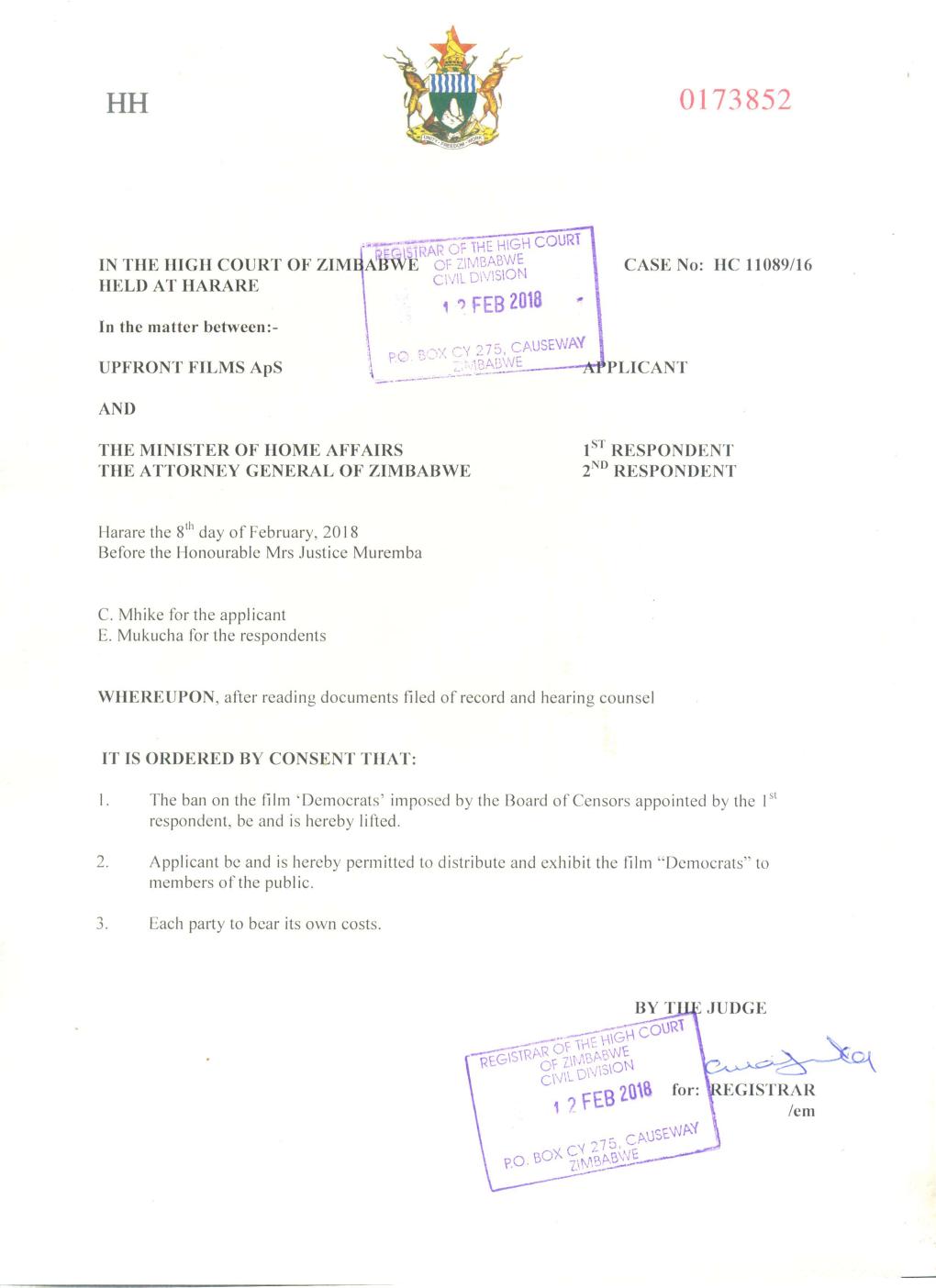

The Board of Censors gave no reason for its ruling, allowing Camilla Nielsson – with help from the human rights organisation Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights – to take her case to Zimbabwe’s Supreme Court, and win.

Popular backing

When the Board of Censors banned the film in 2015, it became a cause célèbre. It had not gone unnoticed that two white Europeans for the past three years had been filming the constitutional negotiations between Mugabe’s party and Morgan Tsvangirai’s opposition party, and people were fed up with the government abusing its power.

"The opposition party started a big campaign with the churches, which are very powerful in Zimbabwe, rallying civil society against the ban. It was communicated throughout the country that the film, about the making of the country’s first democratic constitution, had been banned. This was antidemocratic on such a meta-level that it was almost unbearable," Nielsson says.

"I didn’t make a Mugabe basher. Both parties have approved the film and its content. On the other hand, I’m not surprised the film was banned, because this way of filming politics has never been seen in Zimbabwe before. The country’s media landscape is a little bit like North Korea’s, with one state-owned TV station with government-paid TV presenters, who exclusively do pro-regime propaganda. So, when a Danish documentarian shows up and films politics close up with a handheld camera, the censors almost fall off their chairs."

A test case for freedom of speech

For Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, the case was an opportunity to strike a blow for freedom of speech in the country, where opponents of the Mugabe regime were regularly beaten, imprisoned or killed. On that point, the Danish filmmaker was at an advantage.

"Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights pursued the case on my behalf, not only to put this film about the constitutional talks out there, but also because it was an important test case for press and media freedom. In that regard, it was an advantage that a foreign filmmaker was filing suit," Nielsson says.

"If a local filmmaker had gone for the throat of Mugabe and his government, they would have risked persecution or other repercussions during and after the case. But a Danish filmmaker was a much safer shot in a freedom-of-speech case, because the worst thing that could happen to me was that we lost. They couldn’t drive up to Copenhagen in a black car and take me away."