When a disastrous earthquake hit Haiti on 12 January 2010, Jørgen Leth’s home and life came crashing down.

The Danish filmmaker and writer, based on the Caribbean island since 1991, was pulled from his house in Jacmel, on the south coast, by his long-time assistant, Beleque, who heroically ushered him down the broken stairs, through the garden and into the street, where everything was chaos. Houses were collapsing and bodies were strewn everywhere. Around a million Haitians lost their homes that day. And around 200,000 died.

"It was a horrific experience," Leth says. "I was very lucky to survive. I got a huge shock and seemed to experience everything in slow motion. Suddenly, the walls are gone and everything looks changed."

Making something out of nothing

In an attempt to process both his personal and the national trauma, Leth the following year started filming his daily life and surroundings near the small hotel in Cap-Haïtien, on Haiti’s north coast, where he moved in January 2011 and where he is still living. Using his mobile phone, he filmed a diary and eyewitness account from the ruined country.

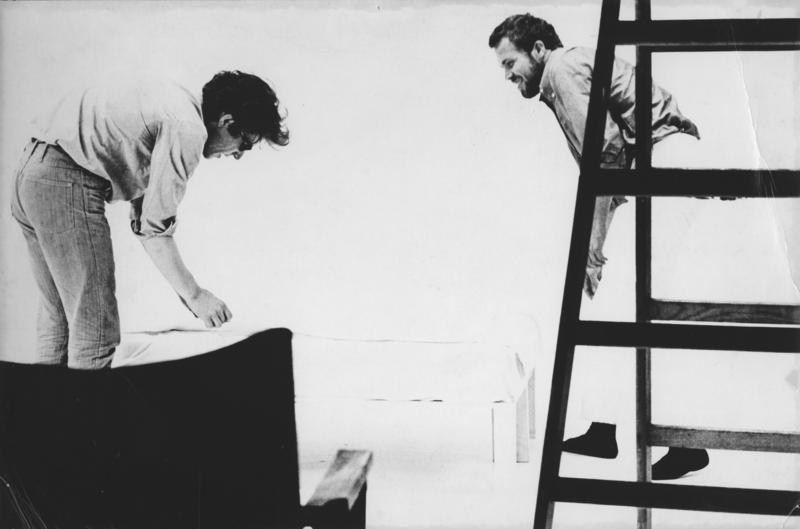

In the beginning, it was about recording what he saw in order to remember it. But when he showed the videos to his son Asger Leth, who is also a filmmaker, Asger convinced him that there was a film there. Realising the potential, Leth kept shooting with even greater focus than before – now with Sigrid Dyekjær as producer, and Jacob Thuesen and Tómas Gislason as sparring partners and editor and camera operator, respectively.

"I had to get my life up and running again and get a handle on what I wanted to do. That’s what the film ended up being about," Leth says. "The basic tension of me walking around in these surroundings, trying to come to terms with life there, held a story. Some strange, sensitive material."

The recipe, which he has worked from a number of times, he calls "making something out of nothing". The film includes home video of Leth reflecting on his situation, street footage, looks back at his past films and a trip to the jungle in Laos. "You could say it’s nothing, but at the same time it’s a lot," he says.

Clip from 'I Walk'

Mobile texture and aesthetics

Jørgen Leth, a central figure on the experimental Danish documentary film scene in the 1960s, has always been preoccupied with exploring the language of film. Shooting 'I Walk', he was captivated by the mobile phone’s "handheld, over-sensitive approach to the elements of reality".

"It’s a whole new aesthetic, a new way of framing images, which inspired me. It was very real. It didn’t have to represent anything. It simply was. The mobile aesthetic gives a fantastic texture and rawness, bypassing a lot of unnecessary decorative devices. I felt I was back at something authentic in myself, the desire to make the material speak directly through the images. I rediscovered a desire to reinvent everything," the filmmaker says.

Leth early on latched on to the title, 'I Walk', because it covers the essence of the film, both concrete and symbolically. Concretely, the shock from the earthquake affected his sense of balance and gave him trouble walking. The film shows him struggling to put one foot in front of the other.

"I had to learn to walk, almost all over again. That may sound simple and trite, but it’s not. It’s something you have to do to get on with your life, and it was a challenge. I think that’s reality," says Leth, who sees the film as an extension of the anthropological investigations of his earlier films.

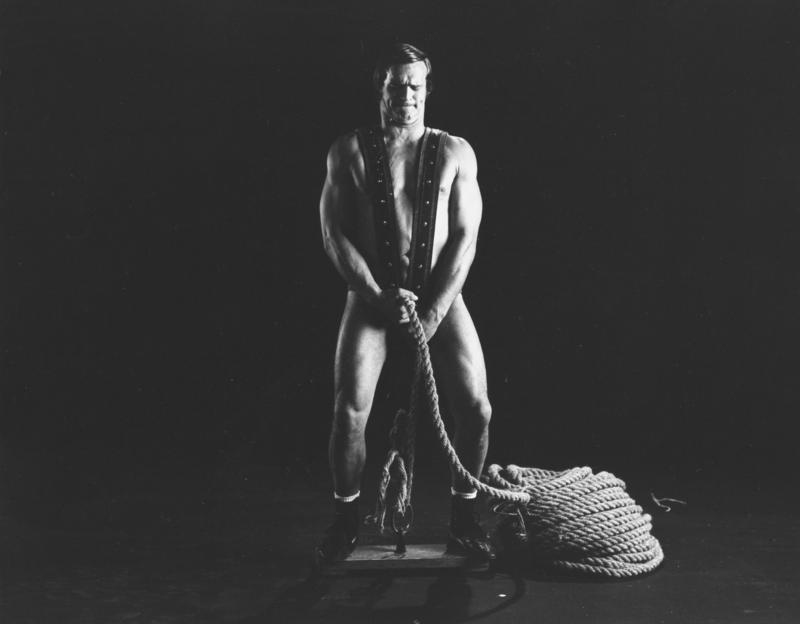

"Simplicity is a recurring element for me. A man that walks. A hand that moves. The elementariness of walking relates to some of my other films, like 'The Perfect Human', 'Good and Evil' and 'Erotic Man', which also deal with elementary movements observed at arm’s length. I like to observe the banal content of life as phenomena, and look at life through a magnifying glass. Then it’s not banal anymore."

Framing chaos

The film also documents Leth’s effort to put a piece of jungle under the magnifying glass. Travelling to Laos with his crew, he hired local workers to physically frame a piece of the jungle, which he describes in the film as "the most concentrated chaos in existence" with no "visible rules."

"It’s a way to make chaos speak. That’s what the film is about. There’s a poetic logic in showing an image of overcoming adversity by occupying a piece of wild nature. This is also illustrated by my effort to walk up a slope in the jungle. I like the idea of the effort involved in capturing a piece of land, seizing it, coming into it, seeing and framing it. This also relates to the artistic method of my past work, where I don’t have the material in advance but tell a story by doing."

Leth, who calls 'I Walk' his "filmic testament," is proud that he managed to rediscover his curiosity, break with convention and simplify the rules for himself by filming with his phone.

He considers the film "one of the most direct and lively films I have made in a long time." At the age of 82, he is not finished making films, or walking. In late October, he had a procedure done on his brain which has already improved his balance. And the "effort" of making the film has whetted his appetite to further explore his expressive potential despite the impediments of age.

"All of a sudden, I had to physically struggle to even express myself. That left me with a different clarity about what I can do, what I’ve been through and what I want to do going forward. I think this film has cleared the way for me."