According to recent UN estimates, 70.8 million people around the world are refugees. Some are fleeing war and bombs, others impossible living conditions and corruption.

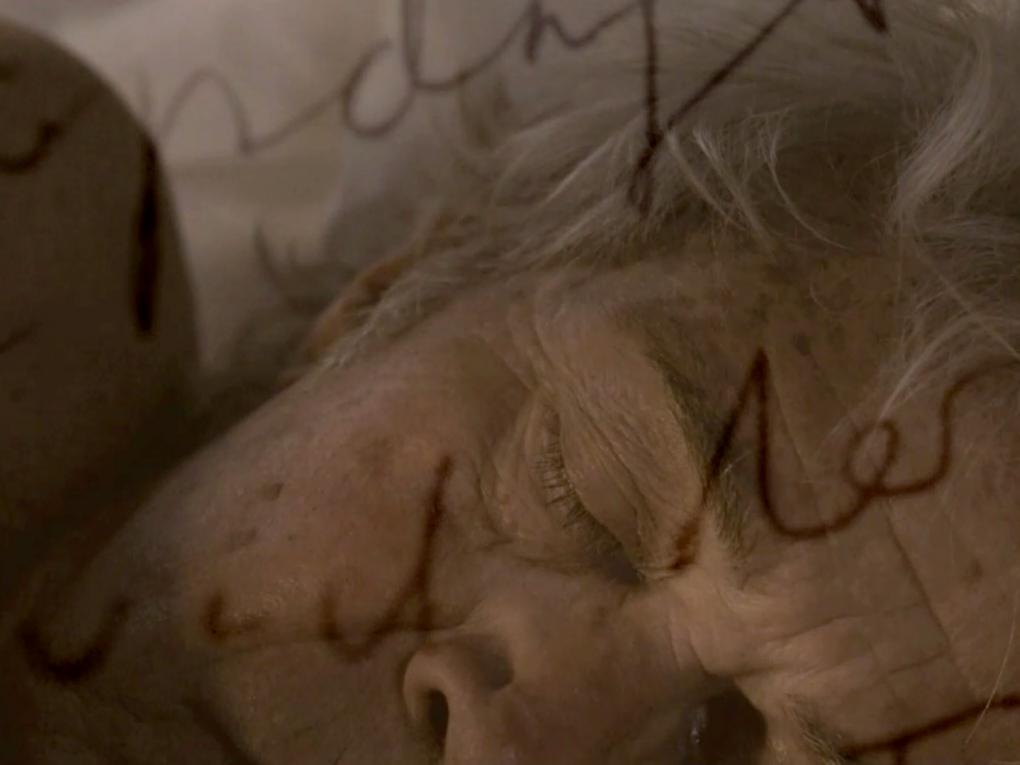

In 'Love Child', an Iranian couple, Leila and Sahand, and Leila's young son, Mani, have fled for love and the dream of a life together as a family. A dream they cannot realise in their homeland, whose strict marriage laws forbid Leila from leaving an unhappy marriage and creating a new life with her lover, Sahand, and their son, who everyone thinks is her husband’s.

In Iran, if worse comes to worse, their infidelity is punishable by death. So the two lovers, who seem to have it all – good educations, stable careers and outwardly happy families – leave it all behind to make a new, uncertain life for themselves as refugees in Turkey.

Hoping they will be more secure if their story is documented, they get in touch with the film’s co-producer Henrik Grunnet and co-director Morten Ranmar, and through them Eva Mulvad, who later takes over the project.

Over several years, the seasoned documentarian and her crew follow the couple’s struggle to establish a new life and a day-to-day routine amidst fear and uncertainty and the loss of all the good things they have sacrificed for their new life. A life full of ups and downs, as the film shows us in depth.

Despite their troubles, the family in 'Love Child' seems better off than most of the refugees we usually hear about in the media. Both parents speak English, are well educated and left behind good jobs and families in their home country, which is not war-torn. Why did you choose to tell their story?

"I wanted to nuance the refugee debate and humanise the statistics by presenting people we can mirror ourselves in. I myself have a lot in common with the two protagonists, Leila and Sahand. I, too, have a son and a small family trinity, and I have seen Bergman films, like they have. So perhaps it’s easier for me, and others like me, to understand them and relate to the tough situation they’re in. Or at least that was the idea.

"For good reason, we have heard a lot about Syrian refugees and immigrants from Africa seeking Europe’s 'promised land'. We don’t often hear a lot about the more resourceful refugees, yet they also exist in great numbers. Obviously, the refugee category is made up of people who are every bit as different and diverse as the rest of us, who aren’t refugees. The film makes the simple point that it could just as well have been you or me."

The film features many heart-wrenching and happy scenes, but it lavishes attention on everyday routines, as well. Why is it important to portray the family’s everyday life?

"While journalism typically deals directly with what’s relevant, a creative documentary couches what’s relevant in a familiar skin. For me, the familiar is in the everyday scenes and the relationship issues between Leila and Sahand. In fact, it’s as much a love story as a refugee story. Personally, it’s in their different ways of reacting and their strong cooperation as a couple that I recognise myself the most."

You filmed the family over six years, from 2012 to 2018. How does following them for so long impact the story?

"Following them over such a long period, we don’t force reality to match the film’s needs. Instead, we keep coming back, again and again, until the story has the right duration, and the characters have the depth and complexity they deserve. That makes the documentary very powerful filmically, I think.

"We capture all the big and small moments of their lives. We see a small boy grow up, and we’re there when he’s told who his father is. We see how the parents and the family come together, and we pick up all the little movements between three people who have been struggling so long to create a new family life for themselves in a very difficult situation. That’s a long and complex process, and we took the time to capture it."

You’re an experienced director who has made films with very different themes. Do you see a thread in your work?

"Overall, I have worked along two lines. There’s the socially relevant and humanist line, which we see in 'Enemies of Happiness', where I track a female Afghan politician bravely fighting for democracy. And there’s the other line, where I’m more interested in the luxurious and decadent – as in 'The Good Life', which takes a close-up look at a family’s extreme fall from wealth to poverty, and 'The Castle', which is about luxury housing for seniors.

"In general, what I’m probably most interested in is the form of my films. I like films with complex stories and characters and no easy solutions. I guess, what I particularly have to offer is a kind of thoroughness.

"I try to make films that stay with you and can hopefully prompt inconvenient realizations and force the audience – including people who usually have a negative view about refugees – to think about what it means to leave behind everything you know and start over again from nothing. I want the audience to put themselves in their shoes."

The article was published 30 August 2019, revised 11 November 2019.