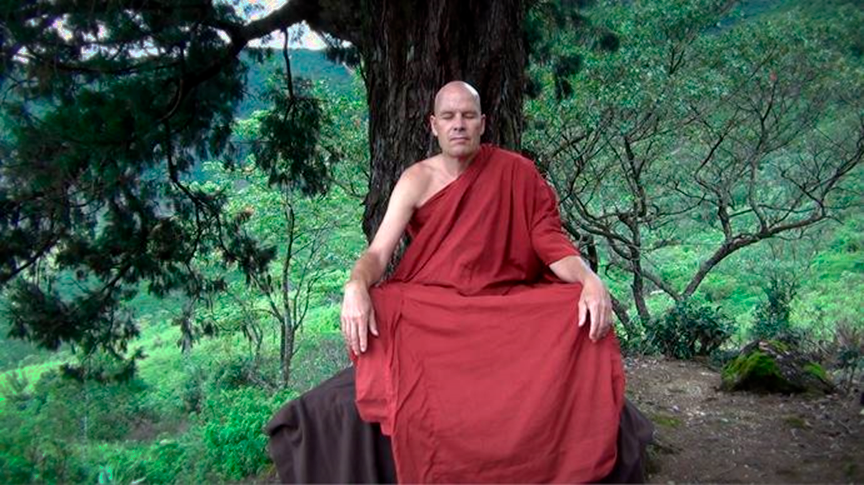

Six years ago, the filmmaking couple Mira Jargil and Christian Sønderby Jepsen decided to jump off the treadmill and went off to a Sri Lankan jungle with their young son to learn to meditate with a Danish Buddhist monk, Jan Erik Hansen. The self-actualisation project was also a work project. Jargil was making a documentary portrait of the monk, who 17 years before had left his family and his successful career in Denmark as a doctor and a leading HIV-treatment researcher.

But after falling out with Larsen a year into the project, Jargil dropped the film and returned to Copenhagen.

Several years later, she came into contact with the monk’s son, Thor, who told her that his father had committed suicide. Thor and Jargil agreed to revive the project. Investigating what was behind the monk’s radical decision, she dived deep into the mysteries of his life and the clues he left behind.

Audience interviews to clarify storylines

Taking numerous twists and turns along the way, the mammoth project, which will become both a film and a documentary series, comprises a vast amount of footage, with at least three different storylines and a meta-layer about the bumpy making of the film.

The director was not sure how to prioritise the storylines, who the real protagonists were or how the audience would experience the story’s different themes and angles. In fall 2021, after a dialogue with the Danish Film Institute, she applied to AudienceFocus, a funding scheme that facilitates and supports audience research already during development.

Working from an extensive question guide, a director’s video, film clips, a teaser and pitches, anthropologists from the Copenhagen-based consulting company Maple in November 2021 conducted in-depth two-hour interviews with 16 audience members from across the country who watch documentaries and have access to national broadcaster TV 2, where the series will premiere. The context of the study was the series’ format.

"To begin with, I was actually a bit sceptical. I wasn’t sure how much could be concluded from a series of interviews with 16 people, and I felt vulnerable about putting my raw material out there to be judged so early on in the process," says Jargil.

"Nonetheless, I applied to the scheme, because I’m incredibly curious and greedy," Jargil laughs. "It turned out to be a huge gift."

Who is the protagonist?

One of the things Jargil wanted a response to was who the true protagonist of the story is.

"We always had a sense that the monk was the protagonist. But looking at it theoretically, it could also be the son, because his character develops, too,” she says.

"The audience study confirmed that the monk is the protagonist. He is the exotic, fascinating character everything revolves around. But the study also showed that he couldn’t stand alone but needed witnesses around him."

Jargil was unsure how much she and her partner and producer Christian should figure in the story. When the conflict with Jan arose, they reflexively turned their camera on the behind-the-scenes drama, without knowing whether the footage would even make it into the film.

"The study showed that a large part of the audience achieves identification through us. Plus, we add some comic relief to a serious story," Jargil says.

All in all, the audience findings created clarity and security, while largely confirming that she was on the right track with the film.

“It confirmed what we already sensed but weren’t sure about. So, we entered the editing phase with a sense of calm but also a heightened awareness of the pitfalls – again, the same ones we had sensed all along. However, sensing something and having it confirmed and feeling certain about it are worlds apart.

"We got to know our material better, and I think we will be able to skip a few steps in the editing because we are more focused now. The conversations about where the fascination lies to an outsider have also given us a language for the story arc that makes it easier to pitch and discuss the film with investors.”

The audience is smart

During the process of making a film, Jargil usually receives feedback from experienced consultants, then holds test screenings for wider audiences before editing the final cut.

"This was something completely different," she says. "It was great to hear the audience’s reactions unfiltered. Normally, most people are polite and couch their criticism carefully before giving it to me, the director. The research audience didn’t know anything about me and gave me their honest opinions about the clips they saw."

Jargil was pleasantly surprised at the audience’s critical readings of the film based on the limited footage presented to them.

"My experience was that the audience is smarter and more perceptive than we give them credit for. They were able to feel and think a lot based on very limited footage. TV generally wants things to be very clear-cut. So, it was invigorating to see that the audience has no problem thinking for itself and that everything doesn’t have to be true crime, completely over-told or overblown to catch their attention," she says.

The research also helped ensure that the characters appear the way she intended.

"I actually think there’s an ethical aspect in testing how the audience perceives a character.

"Of course, you should be protective of the fact that a complex story may provide different experiences, and that there isn’t one truth. But if a majority of the audience perceives a character in a way we didn’t intend, it might be a good idea to go back and see whether something should be underscored or omitted. Sometimes it takes very little. Poring over the footage for a long time can make you immune to the impression a character makes."

Trust your gut

Jargil didn’t act on all the audience feedback, of course.

"I have tried to meditate and trust my gut on whether the feedback speaks to something I have been thinking about, or been worried or enthusiastic about, and in cases when I’m certain the critique would not have existed if the audience had seen an entire film. It’s about being selective and letting the criticism bounce off. I’m not sure audience research would have been a good idea, if this had been my first film. Because that’s a very vulnerable place to be in and you have to find your own language," Jargil says.

Moreover, she’s aware of when in the process audience research is most productive, also when it comes to applying to the scheme again sometime in the future.

"You might be at such an early point in the filming that audience research would knock you top the ground and make you doubt the whole thing. There are no set answers. But the way I work, I feel good about going into a process like this when I have finished the filming and have some thoughts about the editing. It’s important to have an idea about what you want to get out of the research, and if you can’t articulate it yet, it’s going to be hard for others to navigate."